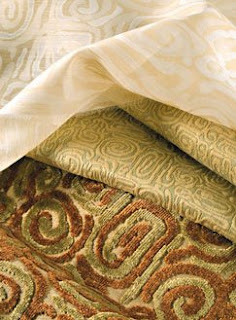

Sina Pearson - Cut and Paste

Sina Pearson - Cut and Paste

Manufacturer: Arndís Jóhannsdóttir.

Product: Fish leather.

Standout: Sturdy, dense, remarkably thin, and waterproof, aquatic hides can be spotted, scaly, or slightly iridescent.

The good thing about living on a sparsely populated island just south of the Arctic Circle is you rarely have to deal with Europe's scuttlebutts. Somewhat problematic, however, are those rare moments—some recent—when you're directly affected by the vicissitudes of the larger market.

Very briefly after WWII, Iceland found itself cutoff from Europe's already scarce supply of raw materials. Since plastics had not yet become a common production material, fish skin was tanned and used in lieu of traditional cow or horse hides. Nearly 40 years later, Reykjavik-based saddle smith Arndís Jóhannsdóttir unearthed some old fish leather in local cellars, and for nearly a decade, she used the skins. Eventually, however, the material became so well received that a fish tannery, shuttered for some 50 years, reopened.

While the tanning process remains a guarded secret, the resulting material is strong, pliable, and unique in texture and pattern. It's used most widely for shoes, purses, bowls, and wall coverings, but Jóhannsdóttir has a new application: tiles made from catfish. 354-8984925

Eco-sensitivity seems to run in India Flint's family: her grandmother used tea leaves, onionskins, and calendula to re-dye clothing; her mother crafted botanical drawings. So it stands to reason that, after wandering the world, this Melbourne native settled on a small family farm in South Australia's Mount Lofty Ranges and pioneered her own fabric dyeing process called the Ecoprint.

Flint stumbled on the method while experimenting with the Latvian technique of wrapping Easter eggs in ferns or leaves, then covering them in onionskins to create a fossilized effect. The designer adapted the idea for textiles by devising a water-based method of applying vegetable color to cloth using small amounts of plant material in a recycled dye-bath. All of the vegetation comes from Flint's farm while the cloth is woven from the wool of her own flock of sheep.

The result is a luxurious bohemian look, a profusion of muted color that resembles delicate, couture quality tie-dye. Look closely at the patterns, and the shapes of eucalyptus leaves and blossoms emerge. Flint's new Watermarks collection of billowy tops and dresses is entirely handmade. For every item she sells, the designer plants a new tree. 61-439-999-379

Despite its considerable charms, America's West Coast is a bit far from home for a subject of the British crown. So, what's a transplanted English rose to do? For Rosemary Hallgarten, her husband, and their two sons, the decision was to trade their home in San Francisco for a 200-year-old barn in Westport, Connecticut. “San Francisco is pretty and livable,” says the jewelry-turned-textile designer who lived on the Left Coast for nearly 13 years, “but I love having the proximity to New York.” She also finds New England, well, more English.

In search of a home to renovate, Hallgarten and her husband Simon, a hospitality property developer, fell in love with the 3,600-square-foot pine barn with its large, light-filled spaces and intact hayloft. Working with Studio 1200 principal and architect Kraig Kalashian, the Hallgartens added 5,000 square feet with a contemporary addition that connects to the original barn via a silo-like entry that houses a circular stair. “In San Francisco, we were in a very small space,” says Hallgarten. Here, “I felt like I had the space to put my own things.”

A texture aficionado, Hallgarten's rich pieces blend beautifully with the barn's antique wood planks and the addition's polished concrete floors. In the hayloft-turned-library, a 3-by-9-foot striped rug of alpaca and leather looks down on the living room's 20-by-25-foot Glaze rug, of hand-knotted alpaca. On Glaze rest alpaca-covered sofas, enhanced with throws of alpaca bouclé and 20-inch-square, hand-embroidered cotton pillows. Elsewhere in the room sits Hallgarten's crotched steel and leather chair, covered in shaggy fringe. An upstairs hallway pays homage to Gloria Finn, Hallgarten's rug-designing mother, who in the 1960's made the 5-by-7-foot New Zealand wool piece found there. Finn's work also appears in the bedroom, via the raised pile, hand-tufted Gio Ponti rug, named for the artist who commissioned Finn to interpret his paintings for the floor. Pillows of Suri alpaca sit on the bed. Amid the sample-packed shelves in Hallgarten's office is her favorite lounge chair, a piece of unknown provenance with moveable arms. Lounging on it, one catches sight of Guenevere, a vine-laden floral inspired by a William Morris painting. Clearly Hallgarten cannot escape her English roots. 203-259-1003